Google CTF 2018: DM Collision (176 pts)

Jun 26, 2018TL;DR: do horrible things to a one-way compression function by leveraging weak keys in the DES block cipher.

You can find the challenge files and my exploit code here.

One-way Compression Functions

A one-way compression function is an important cryptographic primitive that is useful for building secure hash functions. Simply put, it’s a function \(F\) that takes two fixed-length inputs, \(K\) and \(M\), and turns them into a single fixed-length output, \(H = F(K, M)\).

One property we want one-way compression functions to have is collision resistance: it should be difficult to find two pairs \((K_1, M_1)\) and \((K_2, M_2)\) such that \[F(K_1, M_1) = F(K_2, M_2).\] Another important property is preimage resistance: for any output \(H\), it should be difficult to find an input pair \(K, M\) such that \[F(K, M) = H.\]

This challenge defines a one-way compression function based on the DES block cipher, and asks us to break both collision resistance and preimage resistance. Specifically, the compression function operates on a pair of 8-byte strings \(K\) and \(M\) and produces an 8-byte output \(H\). The endpoint asks us for three pairs of inputs: \((K_1, M_1)\), \((K_2, M_2)\), and \((K_3, M_3)\) and verifies that:

\[F(K_1, M_1) = F(K_2, M_2)\]

\[F(K_3, M_3) = 0^8.\]

Here we use the notation \(0^8\) to refer to the 8-byte string consisting of all 0’s.

The Davies-Meyer Construction

The Davies-Meyer construction allows you to build a one-way compression function out of any existing block cipher. It simply XORs the input against the encryption of the input with the key:

\[F(K, M) = M \oplus E(K, M)\] where \(E(K, M)\) is the block-cipher’s encryption of the message \(M\) with the key \(K.\) One can show that if the block cipher is secure (under the “ideal cipher” model), the corresponding Davies-Meyer compression function is collision-resistant.

DES and Weak Keys

Our compression function used DES as its encryption function. (Actually it used a variant of DES with a permuted list of S-boxes; see below). Needless to say, DES is not an ideal cipher, and certain weaknesses in DES allow us to break the security of the compression function.

DES has the unusual property that, for certain “weak” keys, encryption is the exact same operation as decryption. For example for \(K = 0^8\),

\[E(0^8, E(0^8, M)) = M\]

for any message \(M\). Furthermore, weak keys also have substantially more fixed points than average. For example, there are around \(2^{32}\) inputs \(M\) such that

\[E(0^8, M) = M.\]

The precise reasons that these properties occur are not substantially relevant to this challenge but are not too difficult to comprehend if you understand how DES works. The Wikipedia page on DES weak keys explains the first phenomenon, while this paragraph in this paper from 1985 explains the surplus of fixed points.

Breaking Davies-Meyer

To break collision resistance, simply set \((K_1, M_1) = (0^8, 0^8)\) and \((K_2, M_2) = (0^8, E(0^8, 0^8))\). Then,

\[H_1 = 0^8 \oplus E(0^8, 0^8) = E(0^8, 0^8) \] and

\[\begin{eqnarray} H_2 &=& E(0^8, 0^8) \oplus E(0^8, E(0^8, 0^8)) \\\\ &=& E(0^8, 0^8) \oplus 0^8 \\\\ &=& E(0^8, 0^8) \\\\ &=& H_1. \end{eqnarray}\]To break the preimage resistance of the all-0 output, we must first find a fixed point \(M\) such that \(E(0^8, M) = M.\) Then set \((K_3, M_3) = (0^8, M)\). This yields:

\[\begin{eqnarray} H_3 &=& M \oplus E(0^8, M) \\\\ &=& M \oplus M \\\\ &=& 0^8 \end{eqnarray}\]as desired.

Finding a fixed point

All that remains is to find that fixed point. The space of DES inputs has size \(256^8 = 2^{64}.\) We said earlier that \(2^{32}\) of these inputs will be fixed points under a weak key. It follows that we must try \(2^{64-32} = 2^{32} \approx \text{4,300,000,000}\) inputs before we find a fixed point.

The python version of DES that we were provided can compute 1 encryption in about 1 millisecond. At that rate, it would take 50 days before we found a fixed point. But everyone knows that python is slow. Let’s switch to a compiled language to speed things along.

I googled around for a fast version of DES in C, and found this implementation. It can compute 1 encryption in about 20 microseconds. This already brings us down to around 24 hours of computation. We can do even better if we compile it with the -O3 flag: now 1 encryption takes about 4.4 microseconds, corresponding to about five and a half hours of total running time. This is fine for the purposes of the CTF, but it doesn’t give us much room for error.

Luckily, I have access to a 25 core machine. If we spin up, say 16, separate processes, we’ll find a fixed point in around 20 minutes. Great!

Of course, it’s never that simple. The first problem is that the block cipher we were given was not an exact copy of DES; indeed, the python file implementing it was called not-des.py. (If it were an exact copy, we could simply look up and reuse a fixed point that someone else already found). So, our first task was combing through the implementation to spot the differences so that we could modify our C program to match not-des.py.

As I mentioned briefly above, the only modification was a permutation of the eight S-boxes used by DES. All we have to do is rename the eight S-box variables to make it match.

I modified the C code to range over all possible values of the first four bytes of input to explore a total of \(2^{32}\) values, searching for a fixed point. To explore a disjoint space for each of our 16 processes, I compiled 16 versions of the program each with a unique last byte of the input. Each process was spun up with nohup ./des$i > output/des$i.txt &.

After about five minutes of running, I noticed that all of my processes were being killed by the kernel. A little exploration with htop revealed that all my RAM was being eaten up. It turned out that the C code I was using had a memory leak: it was mallocing 8 bytes for every encryption and never freeing the memory.

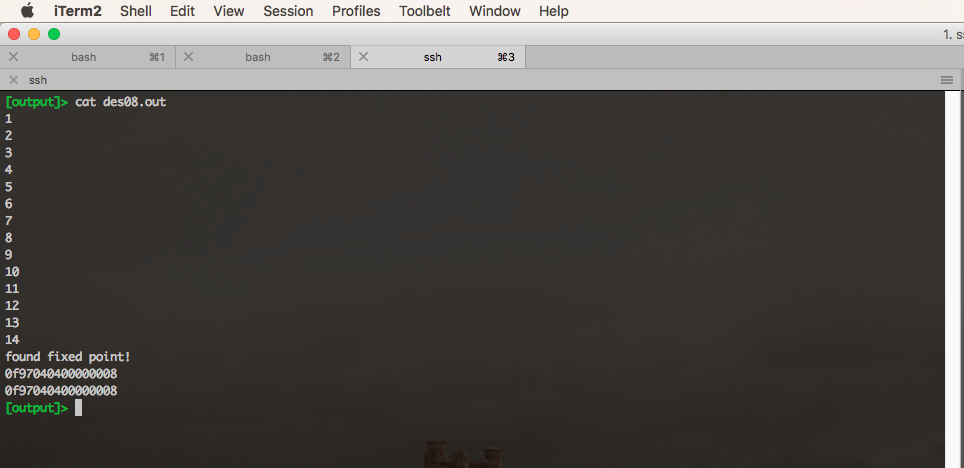

Once I fixed this issue, it was smooth sailing. Process #8 ended up being the first to locate a fixed point:

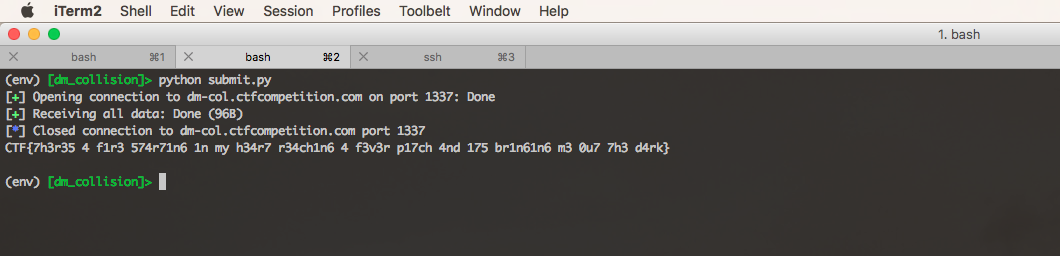

Getting the flag

We can compute \(E(0^8, 0^8)\) as 0x7c0b7ee5a4b22be0. Our fixed point is 0x0f97040400000008. With these two values in hand, we can write a dead simple pwntools script to get the flag:

from pwn import *

r = remote('dm-col.ctfcompetition.com', 1337)

r.send('\x00' * 8)

r.send('\x00' * 8)

r.send('\x00' * 8)

r.send(unhex('7c0b7ee5a4b22be0'))

r.send('\x00' * 8)

r.send(unhex('0f97040400000008'))

print r.recvall()

The flag is: CTF{7h3r35 4 f1r3 574r71n6 1n my h34r7 r34ch1n6 4 f3v3r p17ch 4nd 175 br1n61n6 m3 0u7 7h3 d4rk}.