The Genetic Book of the Dead

Feb 16, 2025Beautifully illustrated and well-written, Richard Dawkins’ newest work The Genetic Book of the Dead is a wonderful read for anyone who is interested in wildlife, anyone who enjoyed learning about genetics in high school and wants to think more deeply about that subject, and anyone who enjoys an extremely technical mind write lucidly about a topic he loves.

Below I’ve summarized a few of the book’s most interesting sections.

The Astonishing Power of Convergent Evolution

A familiar sight to any North American wildlife enthusiast is a Turkey Vulture soaring in the sky, riding the thermals and looking for deceased animals it can harvest for food. North America has other vultures too, including the Black Vulture and California Condor. Remarkably, these “New World” vultures are not genetically related to the “Old World” vultures, despite their similar names, appearance, and behavior.

Such is the power of convergent evolution: natural selection, applied over a long enough time frame, can result in genetically distinct species that exhibit remarkably similar traits. The Old and New World biomes (species of Eurasia and Africa vs. species of The Americas) provide many excellent examples: New World porcupines are not related to Old World porcupines, nor are American badgers closely related to European badgers:

Going clockwise starting from the top left is the American badger, European badger, African Honey badger, and Chinese ferret-badger. The first and third are only distantly related to the second and fourth.

The island of Australia, populated mostly with marsupials rather than placental mammals, provides many more examples of convergence: it has a false anteater, called the numbat, a false flying squirrel called the sugar glider, a false mole, false mouse, and even a (now extinct) false dog. The book contains a beautiful side-by-side illustration of each species and its placental counterpart.

Convergent evolution also can result in convergences of traits rather than entire species. For example, powered flight has independently evolved at least four times in Earth’s history: in bats, in birds, in pterosaurs, and in insects. Electric organs (such as those used by electric eels) independently evolved at least six times.1

The Backward Gene’s Eye View

Dawkins’ central thesis of his most famous book, The Selfish Gene, is that of the gene-centered view of evolution, which names the gene as the fundamental unit of selection in evolution. Natural selection operates on genes, not individuals or species, because it is genes themselves that either are or are not passed on to offspring.

There is a significant difference between a ‘people tree’ and a ‘gene tree’. An individual person has two parents, four grandparents, eight great grandparents, etc. So a people tree is a vast ramification as you look backwards in time. Any attempt to draw it out completely will soon get out of hand. Not so the gene tree… …A gene has only one parent, one grandparent, one great grandparent, etc. A gene tree is therefore a simple linear array streaking back in time, whereas a people tree bifurcates its way unmanageably into the past.

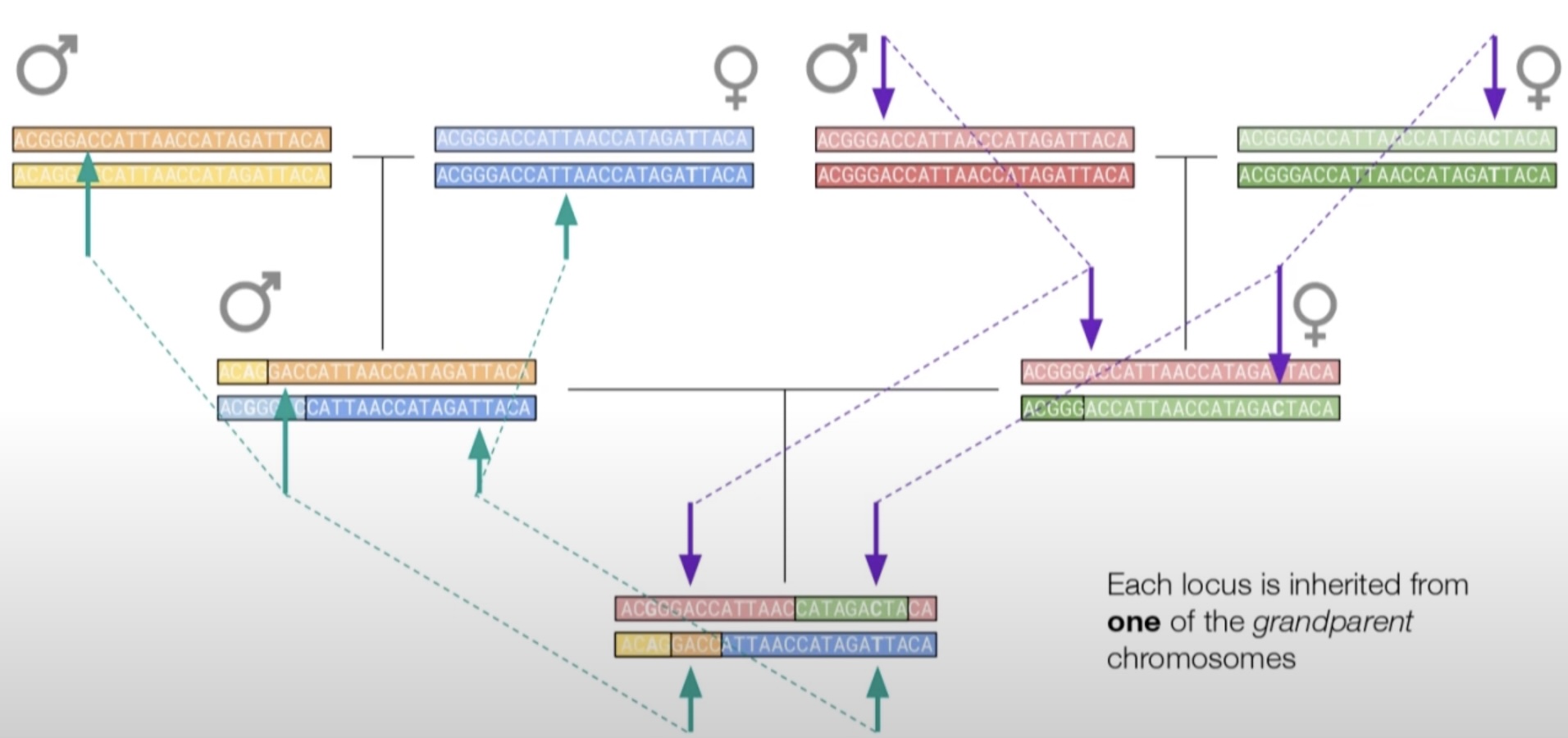

You have two copies of every gene in your body, one from each parent. The copy that came from your father came either from your paternal grandfather OR your paternal grandmother. Your mother’s copy of the gene came from your maternal grandfather OR your maternal grandmother. You can trace each copy backwards across generations and the two lines will eventually meet in a common ancestor: an actual, physical person with (at least) two children: this person gave one copy of the gene to one child (who is a direct ancestor of your father) and the other copy to another child (a direct ancestor of your mother).

This common ancestor is unique to each gene—different genes will converge at different points.

Naively, you might expect that a given chromosome is an exact copy made up of one half from a maternal grandparent and another half from a paternal grandparent, but while this is true on the gene level, it’s not true at the chromosome level: you’ll notice that the chromosome illustrated above contains fragments from all four grandparents. This is due to crossing-over. During meiosis when sperm and egg cells are produced, each chromosome sometimes exchanges segments between individual chromatids (the two halves of a chromosome).

This occurs about 1-3 times per chromosome per meiosis, and intriguingly happens significantly more often in eggs compared to sperm.

Because crossing-over happens at a relatively consistent and low frequency, it can be used to measure the “age” of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for different genes. Basically, in a region of the genome where the mother and father segments are nearly identical, the MRCA is likely fairly recent since there hasn’t been much time for crossing-over to introduce higher diversity. Conversely, if the two segments differ substantially, that suggests that the MRCA is further into the past. This is the fundamental principle behind coalescent theory.

What can you do with this information? Many interesting things; Dawkins describes working with a colleague to sequence his own genome and perform this analysis. When he clustered each region of his genome by MRCA time he discovered that many of his genes date back to ~50,000 years ago, suggesting that his ancestors experienced a population bottleneck around that time.

Scientists have also used similar analysis to show that the LCT gene, responsible for the production of lactase evolved fairly recently—about 7,500 years ago, suggesting that it was naturally-selected as it conferred an advantage in humans around that time (the ability to consume milk from domesticated animals).

A good explanation of coalescent theory can be found in this video:

On Cuckoos

This is the chapter that spurred me to pick up the book in the first place. I’d heard Dawkins discuss this topic in an interview of Dawkins by (fr)e(ak)conomist Steven Levitt.

Many species of cuckoo are brood parasites, meaning that they lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. The eggs are then incubated and raised by the host mother, often at the expense of the the other nestlings.2 As you might expect, there are evolutionary pressures for the host species to reject these parasitic eggs and pressures on the cuckoo to produce eggs that are less likely to be rejected.

As a result, cuckoo eggs exhibit astonishing mimicry of their host species:

On the right are two eggs of the Marmora’s warbler and to the left is a cuckoo egg (cuckoos are larger than their hosts and as a result their eggs can be distinguished by being slightly larger than the host’s eggs3).

Below is a similar example for the eggs of the Moussier’s redstart:

And finally, one more example for the eggs of the European robin:

Mimicry in the animal kingdom is always fascinating, but what takes the story of the cuckoo to a new level is the following: the eggs of all three cuckoos in the examples above belong to the same species (the Common cuckoo).

How can female cuckoos of the same species tailor the eggs they lay to look exactly like the hosts they parasitize? Are there simply subspecies of the Common cuckoo each of which choose to mimic a different host?

Close, but not quite: while a female cuckoo will almost always parasitize the same species of the nest that she was laid in (a female cuckoo raised by a Reed warbler nest will lay her own eggs in Reed Warbler nests, a female cuckoo raised by a Common redstart will parasitize only Common redstarts), male Common cuckoos will happily interbreed with all these females, regardless of the nest they were laid in.

If we consider the backward gene’s eye view, this should be a difficult outcome for evolution to produce: a gene on the Common cuckoo’s genome looks backwards at ancestors that parasitized a whole mix of different species (because of those unchoosy males)—there should be no selective pressure to so closely match the appearance of any given egg.

But—not all the genes have this property. Birds, like humans, have sex chromosomes that are responsible for determining the sex of an individual. Human females have two sets of X chromosomes and human males have one X and one Y chromosome. The Y chromosome is copied directly from father to son. While genes on the somatic (non-sex) chromosomes look backwards at both male and female ancestors, genes on the Y chromosome look only backwards at male ancestors.

Birds operate similarly, although their sex chromosomes are denoted Z and W. However, in birds ZZ individuals are males while ZW individuals are females: thus, a gene on the W chromosome looks backwards only at female ancestors. This resolves the conundrum: the genes controlling egg color must be located on the W chromosome; this allows these genes to specialize to the appearance of the host. The gene of a female cuckoo laid in a European redstart nest looks back at a line of (exclusively female) ancestors all of which were raised by Redstarts and laid their own eggs in Redstart nests. Mutations in this gene that resulted in better matches to Redstart eggs would result in greater probabilities of survival and a greater chance at being passed on.

Dawkins’ Mathematical Mind

Finally, Dawkins frequently includes some asides that hint at how his mind finds mathematics lurking in non-obvious places.

For example, here’s an excerpt pulled from a discussion about sea turtles vs land turtles:

From any point inside an equilateral triangle, the lengths of perpendiculars dropped to the three sides add up to the same value. This provides a useful technique for displaying three variables when the three are proportions that add up to a fixed number such as one, or percentages that add up to 100.

This is a pithy explanation for the workings of a ternary plot. Common examples include flammability diagrams use % methane, % nitrogen, and % oxygen:

Or soil texture charts which use % clay, % silt, and % sand:

Here’s another excerpt from an endnote:

Once, in the Kruger National Park, I came upon the urine trail that a male elephant in musth had made in the dust. It looked approximately sinusoidal, and had evidently been made by his dribbling penis swinging as a pendulum. I photographed it with a vague idea of getting a mathematician to Fourier analyse it and compute the length of his penis.

The period of a physical pendulum is given by:

\[T = 2\pi\sqrt{\frac{I}{mgd}}\]

where:

- \(I\) is the moment of inertia of the pendulum about its pivot point

- \(d\) is the distance from the pivot point to the center of mass

- \(m\) is the mass of the rod

- \(g\) is the acceleration due to gravity

If we model the penis as a uniformly-dense rod of length \(l\) the moment of inertia is:

\[I = \frac{1}{3}ml^2\]

So the period is:

\[T = 2\pi\sqrt{\frac{\frac{1}{3}ml^2}{mg\frac{1}{2}l}} = 2\pi \frac{2l}{3g}\]

So yes, the length is derivable from the period, but from the photo alone we’d need to make some assumptions about the walking speed of the elephant in order to translate from wavelength to period.

Footnotes

-

Darwin used this example in One the Origin of Species when discussing convergent evolution: “But if the electric organs had been inherited from one ancient progenitor thus provided, we might have expected that all electric fishes would have been specially related to each other…I am inclined to believe that in nearly the same way as two men have sometimes independently hit on the very same invention, so natural selection, working for the good of each being and taking advantage of analogous variations, has sometimes modified in very nearly the same manner two parts in two organic beings” ↩

-

This is actually the origin of the term cuckold. ↩

-

Why doesn’t the host “learn” to reject larger eggs? The book does not provide an answer, but perhaps its because the drive to reject large eggs would also result in rejecting larger (and usually, healthier) “true” eggs. ↩