Mystery Hunt 2026

Jan 24, 2026

This post is about the 2026 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with most of the puzzles and solutions at puzzmon.world.

Thanks to Cardinality for writing an excellent hunt this year. I had to decide between participating in hunt for my 12th(!) time in person vs. attending the birthday of a very dear friend; I chose hunt in part because I was convinced that Cardinality would make it worth my while, and they did not disappoint. I experienced generally clean puzzles, novel round concepts, and a lot of fun. Below I’ll cover a few notable points.

Read more...The Genetic Book of the Dead

Feb 16, 2025

Beautifully illustrated and well-written, Richard Dawkins’ newest work The Genetic Book of the Dead is a wonderful read for anyone who is interested in wildlife, anyone who enjoyed learning about genetics in high school and wants to think more deeply about that subject, and anyone who enjoys an extremely technical mind write lucidly about a topic he loves.

Below I’ve summarized a few of the book’s most interesting sections.

The Astonishing Power of Convergent Evolution

A familiar sight to any North American wildlife enthusiast is a Turkey Vulture soaring in the sky, riding the thermals and looking for deceased animals it can harvest for food. North America has other vultures too, including the Black Vulture and California Condor. Remarkably, these “New World” vultures are not genetically related to the “Old World” vultures, despite their similar names, appearance, and behavior.

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2025

Jan 26, 2025

This post is about the 2025 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with most of the puzzles and solutions at two-pi-noir.agency.

My two favorite Mystery Hunts are the 2015 hunt (20,000 puzzles under the sea) and the 2018 hunt (Operation: Head Hunters). Death & Mayhem wrote the latter, so I was super hyped for this year’s hunt, which was also written by them. Overall, it largely met my lofty expectations, while maybe not quite ranking as my favorite hunt of all time.

Read more...A List of Notable Eclipses Through the Years

Apr 04, 2024

In celebration of the upcoming eclipse crossing North America on April 8th, I’ll be posting one eclipse-related post per day. You can see the full list of posts here.

May 3, 1715 - Known as Halley’s Eclipse after Edmond Halley of comet fame, who successfully predicted this eclipse for the first time in human history. London was in the path of totality.

Read more...The Moon Illusion

Apr 03, 2024

In celebration of the upcoming eclipse crossing North America on April 8th, I’ll be posting one eclipse-related post per day. You can see the full list of posts here.

Read more...When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie, that’s… an optical illusion that scientists don’t fully understand.

Augusto Monterroso's El Eclipse

Apr 02, 2024

In celebration of the upcoming eclipse crossing North America on April 8th, I’ll be posting one eclipse-related post per day.

Today, let me recommend to you Augusto Monterroso’s short story El Eclipse, about a total solar eclipse in Central America. You can read the original Spanish text here and an English translation here.

Read more...The Math behind the Eddington Expedition

Apr 01, 2024

In celebration of the upcoming eclipse crossing North America on April 8th, I’ll be posting one eclipse-related post per day. Today’s post is about the 1919 Eddington Expedition and the math behind the theoretical light deflections that were being measured.

In 1919, English astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington embarked on a journey to the island Príncipe off the west coast of Africa in order to witness a total solar eclipse. His goal? To test a novel theory put forth by a certain German physicist a few years earlier: general relativity.

Read more...2023 Paired Book/Movie Recommendations

Feb 03, 2024

I wanted to write down some thoughts on the best books I read and movies I watched in 2023, but to make the exercise a little more interesting I decided to pair each book with a movie and talk a little bit about the connections between them.

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2023

Jan 18, 2023

This post is about the 2023 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with most of the puzzles and solutions at puzzlefactory.place.

This past Monday was the third Monday in January which means that another Mystery Hunt has come and gone. For the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic started, hunt was held in-person on MIT’s campus this year. As you’ll see, I was absolutely delighted to be back.

Read more...Google CTF 2022: Enigma (373 pts)

Jul 16, 2022

Enigma was a cryptography challenge in the 2022 Google CTF in which the goal was to decrypt a message encrypted with the Enigma machine.

The cracking of the Enigma machine by Allied codebreakers during World War II burst into popular culture with the 2014 film The Imitation Game (a fine film, but rife with historical inaccuracies). I myself first learned about it much earlier when I read Simon Singh’s fantastic The Code Book which describes the history of cryptography from the Caesar cipher to RSA, and devotes a chapter to the cracking of the Enigma.

As the README of this challenge explains, Alan Turing and his fellow codebreakers at Bletchley Park never did manage to completely break the Enigma. Instead they developed what in modern cryptography we’d call a known-plaintext attack, in which they made assumptions about particular words and phrases (they called them “cribs”) that appeared early in the plaintext and leveraged those guesses to discover the key. In practice this was good enough to decrypt a substantial number of German messages, but what this challenge asks us to accomplish is what Turing did not: decrypt a German message without any knowledge about its plaintext.

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2022

Jan 22, 2022

This post is about the 2022 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with most of the puzzles and solutions at bookspace.world.

After over ten years of participating, my team finally won the MIT Mystery Hunt for the first time last week! In this post I’ll talk about my hunt experience.

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2021 [Part 2/2]

Feb 20, 2021

This post is the second of two entries about the 2021 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with most of the puzzles and solutions at puzzles.mit.edu/2021. You can find my first post here.

Here, I’ll talk about some puzzles I have thoughts on. These are necessarily puzzles that I contributed to (you can find a list of those here). There will be heavy spoilers throughout!

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2021 [Part 1/2]

Jan 28, 2021

This post is about the 2021 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with most of the puzzles and solutions at puzzles.mit.edu/2021.

Two weeks ago, the 41st annual MIT Mystery Hunt—a project that I’d been working on for the past year—came to a thrilling close. Huge congratulations to Palindrome for being the first team to find the coin. I intend to write two posts about my experience on the writing team. The first (this one) will focus on some of the major events leading up to hunt itself, from theme selection, to dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, to last-minute fire-fighting. In the second, I’ll talk about specific puzzles and rounds that I have things to say about.

I’m sure most people who end up reading this are familiar with the details of how our hunt worked, but I figure it can’t hurt to start out with some context:

Read more...My Votes on the 2020 CA Propositions

Oct 10, 2020

For over a hundred years, the state of California has allowed its voters to enact legislation via a direct yes or no vote through its proposition system. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.

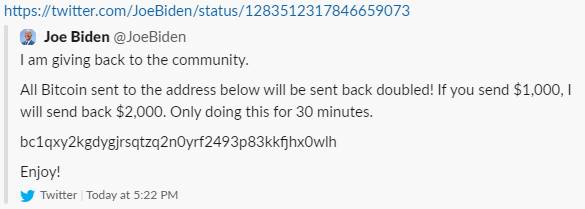

Read more...No, you couldn't have made more money than the Twitter hacker

Jul 15, 2020

Picture this: you’ve stumbled across the vulnerability of the year. You figured out how to gain access to any verified Twitter user’s account: Joe Biden, Kim Kardashian, Kanye West, XXXTentacion, Apple, you name it. That was step 1 of your evil plan. What should step 2 be?

Maybe you log into the president’s account and post a fake tweet about launching missiles to North Korea. I’m not convinced that you can start a world war just by sending out a few fake tweets, but for the sake of argument let’s say that you can. But you’re not interested in watching the world burn anyway; no, your goal is to make as much money as possible. What should you do?

The people who carried out today’s Twitter hack had one answer: post variants of the message “send 1 BTC to this address and I’ll send 2 BTC back” on famous accounts, and then (here’s the kicker) don’t actually send 2 BTC back.

They managed to run off with a little over $100,000 before Twitter got the situation under control. Several people (on Twitter, on Hacker News, everywhere really) scoffed at this and claimed that they would have done something much more interesting with this kind of power. Let’s explore some of their ideas to see if we really can do better.

Read more...Mystery Hunt Team Name Origins

Feb 04, 2020

This is a post about the 2020 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with all the puzzles and solutions here.

I’m still working on a blogpost about some of my favorite puzzles from the 2020 hunt, but in the meantime I thought I’d throw together a quick post about the origins of the team names of various Mystery Hunt teams. Most of this data is collected from these two reddit threads. If I got anything wrong do let me know and I’ll be sure to correct it. Teams after Left Out are sorted by their ranking in this year’s hunt.

Left Out: The name comes from the fact that Left Out has an abnormally large contingent that hunts from the west coast (and so are generally “left out” of hunting on site).

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2020

Jan 25, 2020

This post is about the 2020 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with all the puzzles and solutions here.

I spent the past weekend in Cambridge, MA participating in the MIT Mystery Hunt for the sixth time. I was the captain of teammate, a rather new team that split from ✈️✈️✈️Galactic Trendsetters✈️✈️✈️ (the eventual winners of this year’s hunt) in 2018, and whose increasingly strong performance has taken many by surprise.

Read more...What will happen if I start doing X for various values of X?

Sep 17, 2019

Here are the answers so that you don’t have to waste your time trying it out:

Read more...Quick recs

Jun 23, 2019

These are a few of my favorite things.

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2019 [Part 2/2]

Jan 23, 2019

This is the second of two posts about the 2019 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with all the puzzles and solutions here, and read my first post about the hunt theme and my experience.

Here’s the obligatory list of my favorite puzzles from this hunt:

Read more...Mystery Hunt 2019 [Part 1/2]

Jan 22, 2019

This is the first of two posts about the 2019 MIT Mystery Hunt. You can see the hunt website with all the puzzles and solutions here, and read my second post about specific puzzles I enjoyed.

This past Monday was Martin Luther King Jr. Day, which means that another Mystery Hunt has come and gone. For the second time, I hunted with teammate, which consists of a core group of MIT undergrads and recent alumni joined with several other puzzlehunting groups from CMU, Stanford, Berkeley, and a smattering of solvers from across the globe. The dominant feature of our team is definitely our age: almost all of us are in our early to mid-twenties. We had 90 people on our roster, which in practice meant something like 40 on-site solvers and around 10 active remote solvers.

Read more...New Year, Nutrition

Jan 17, 2019

I find nutrition fascinating. It’s one of the most important research fields given how many people care about its effect on longevity, weight loss, and overall health, but it’s also one of the most difficult areas of science for us to make reliable progress. Part of the problem is that the human body and its metabolism is ridiculously complicated, so it can’t be easily broken down to first principles like physics or chemistry.

As a result, most people are wildly misinformed about some fundamental facts. Here are 9 statements that we know to be true, but that you probably weren’t aware of.

Read more...Hate-watching the Midterms

Oct 18, 2018

On the evening of November 6th, I’ll be watching the results come in for the 2018 midterm elections. You should too. There are many ways to experience the event: maybe you want to watch Wolf Blitzer repeatedly state the obvious on CNN. Maybe you want to incessantly refresh Nate Silver’s twitter feed. Maybe you want to spend all night with your eyes glued to a jittering needle.

There are 435 House seats, 34 Senate seats, 36 Governor’s mansions, 1 Mississippi special election, thousands of state legislative seats, and hundreds of ballot initiatives up for grabs. The midterms can be a little overwhelming.

I think it’s helpful to pick a handful of races that you’re interested in for one reason or another, and follow these all night. Here, I’ve described 10 races that I plan to watch. They were chosen not because of their political importance or their competitiveness, but because each represents a chance to deny elected office to a truly awful human being.

Read more...Google CTF 2018: DM Collision (176 pts)

Jun 26, 2018

TL;DR: do horrible things to a one-way compression function by leveraging weak keys in the DES block cipher.

You can find the challenge files and my exploit code here.

Read more...Anatomy of a Man-in-the-Middle Phishing Campaign on Coinbase

May 29, 2018

In the summer after my freshman year of college, I had an internship with a startup that tries to defeat phishing attacks against enterprise corporations. As such, I spent a lot of time staring at phishing sites. Once, I showed a phishing campaign against MIT’s OWA email portal to my boss, and he blew my mind when he dug through the site and managed to find a publicly-accessible text file where the attackers were logging all the password attempts.

Ever since, I’ve been trying to replicate that same experience on every phishing attempt that comes my way, and for the first time since then, I managed to do it! The attack was targeting Coinbase, probably the most popular site for buying and selling cryptocurrencies. I’ll first describe the campaign, and then show how I discovered the password log file.

Read more...DEF CON Quals 2018: official (194 pts)

May 07, 2018

TL;DR: a 1 byte overflow allows you to induce a small bias in the nonce used in the DSA signing algorithm. Use LLL to exploit this bias to find the private key.

I also explore a more natural variant of the problem in which the bias is in the most significant byte of the nonce rather than the least significant, and recover the private key in this case as well.

Read more...Plaid CTF 2018: Wait Wait... Don't Shell Me (125 pts)

May 07, 2018

This problem was categorized under “Misc” and was worth only 125 points. Nevertheless, it was one of the harder challenges and received only 14 solves. ghostly_gray, fasano, and I worked on it for several hours over the course of the CTF, but we only solved it after the CTF had ended.

The challenge was themed around the NPR Quiz Show Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! and consisted solely of an address and port to connect to.

Read more...Blaze CTF 2018: shellcodeme (420 pts)

Apr 23, 2018

This was a simply-posed but tricky pwnable that ghostly_gray and I solved over the course of a long plane ride. We were given the source code (shown below) as well as the binary. Simply put, we had to write some x86-64 shellcode that used no more than 7 distinct bytes.

Read more...MIT Mystery Hunt 2018: The Puzzles

Jan 17, 2018

This year’s mystery hunt ended last Monday, and after a heroic effort, my team managed to be the twelfth and final team to finish. This hunt did have fewer puzzles than usual, but I don’t think anybody noticed. Puzzle quality was generally high across the board, and since the puzzles themselves were often longer than average (I think), it was all a wash. Below I’ve highlighted some puzzles of note (spoilers abound!):

Read more...New Year, Newsletters

Jan 10, 2018

One form of content that made a resurgence in my media diet last year was the newsletter. Like podcasts, newsletters have been around since the early years of the internet. Their appeal is obvious: instead of regularly visiting a website to read the news, just have it emailed straight to your inbox. I’ve found that newsletters are often better at providing context and perspective than traditional news outlets, which are often too busy breathlessly reporting latest-breaking updates.

Here are five newsletters that I’m currently subscribed to that I think are worth your time:

Read more...Survey of Discrete Log Algorithms

Dec 03, 2017

In 1999 Dan Boneh published a survey paper called “Twenty years of attacks on the RSA cryptosystem”. I like to tell people that if they read the entire paper they can solve just about every CTF challenge involving RSA.

This post is my attempt to do something similar with the discrete log problem, a primitive that underlies a bunch of cryptographic protocols including the Diffie-Hellman key exchange and the ElGamal encryption system. The algorithms all have similar-sounding names, and I wanted to just sit down and describe each of them to get them straight in my head.

Read more...CSAW CTF 2017: Realism (400 pts)

Sep 18, 2017

This problem was much like any other CTF reversing challenge, but instead of a Linux or Windows executable, the binary was a Master Boot Record (MBR) that needed to be run under the QEMU full-system emulator.

We’re given the command to boot the MBR, qemu-system-i386 -drive format=raw,file=realism, and we’re presented with this:

Simple, right? The entire MBR is only 512 bytes in size, so it’s not much to reverse.

Simple, right? The entire MBR is only 512 bytes in size, so it’s not much to reverse.

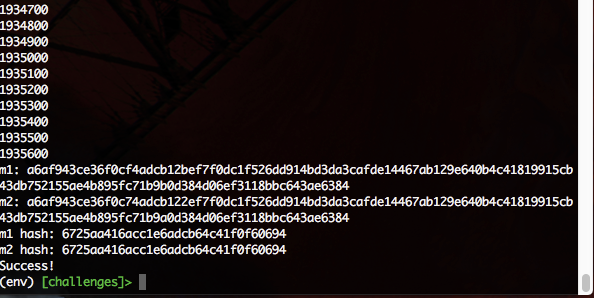

Finding Collisions in MD4

Sep 10, 2017

On and off for the past couple of years, my friend Ray and I have been working through the Cryptopals Crypto Challenges, a series of exercises split across eight sets that explore modern cryptographic protocols and their weaknesses. The challenges start out pretty easy, but as you move forward, the attacks you’re asked to implement become increasingly difficult.

This post is about challenge 55, “MD4 Collisions.” In it, you’re asked to implement Wang’s 2004 attack on the MD4 hash function. The attack itself is pretty difficult: as far as Ray and I can tell, no one has posted a solution to it online. (There is this code from Bishop Fox, but it consists solely of a dense, 500-line, uncommented C program).

After several days of work, our script finally spit out a brand new collision:

In this post we’ll talk about the attack and our implementation in detail.

Read more...GoogleCTF 2017: RSA CTF Challenge

Jul 02, 2017

We are first presented with a simple HTML form that asks us to sign the word challenge in order to login. If we look at the source of the page, we find a hidden div that includes an RSA public key and references to base64 encoding and PKCS1v1.5 / MD5. Our goal then seems to be to forge a signature for challenge in PKCS1v1.5 format that will be accepted by the given public key.

If done properly, this is impossible, but because PKCS1v1.5 is such a brittle scheme, minor errors in its implementation can result in major security vulnerabilities.

Read more...A guide to MIT's campus network changes for the non-expert

Jun 26, 2017

There’s been a lot of buzz on dorm mailing lists and online forums about the changes that IS&T is making to MIT’s campus network. This post attempts to break down and explain the changes to a non-expert in networking in order to clear up some of the confusion surrounding the discussion.

First, a brief introduction to IP addresses and Network Address Translation (NAT):

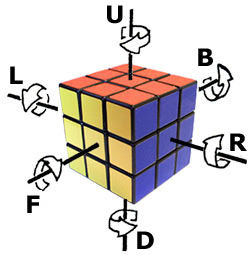

Read more...GoogleCTF 2017: Rubik

Jun 25, 2017

GoogleCTF 2017 was held about a week ago; it was pretty difficult, but it had some cool challenges. This writeup is about one of the harder crypto challenges, Rubik.

We were given some Rust code that implements a version of Stickel’s Key Exchange protocol for the Rubik’s Cube Group. We were also given a service which executes this protocol and allows users to register public keys and login. Before we dive into the details of the protocol and the attack, let’s talk a little bit about Rubik’s Cubes.

Rubik’s Cube Theory

To talk about a series of moves that can be applied to a Rubik’s Cube, most people use Singmaster Notation. The six letters R, L, U, D, F, and B describe 90 degree clockwise turns to each of the six faces. A prime after a letter indicates a counter-clockwise turn. Finally, the letters x, y, and z, describe rotating the entire cube 90 degrees clockwise on the R, U, and F faces respectively. A prime after these letters describes the corresponding counter-clockwise rotation.

This site allows you to apply a series of moves to a cube to explore the notation.

Read more...DEF CON Quals 2017: A story told through pictures

May 06, 2017

Last weekend was DEF CON Quals 2017, the annual qualifier round to the DEF CON CTF held in Las Vegas every year. Last year I tried the CTF on my own and managed to solve 1 challenge. This year I participated on Lab RATs, a joint collaboration between MIT Lincoln Labs, RPISec, and TechSec.

My friend Ray already recapped most of what went down during the weekend on his blog, so I don’t really feel the need to repeat any of it. Instead, let me tell the story of my past week entirely through pictures:

Read more...Configuring a Beaglebone Black as an Access Point

May 02, 2017

A few weeks ago some friends and I competed in the Google Games, a sort of hybrid between a puzzlehunt and a coding competition. It was a fun event, and we managed to come in first! As a prize, each member of our team received a slick backpack and a Google Home, a smart speaker like the Amazon Echo, but designed and built by Google.

Unfortunately, the Google Home (and for that matter all Chromecasts) can’t operate on MIT’s WiFi network because they use Universal Plug and Play (UPnP), a protocol that MIT blocks.

One common workaround to this issue is to setup a personal access point wired into the MIT network that the Google Home can then connect to. I didn’t have an access point lying around, but I remembered that I did have a BeagleBone Black that I got from an IAP Internet of Things class a couple years ago. I decided to configure it to function as an access point.

I’m not much of a tinkerer, and the resulting process ended up being fairly involved. It wouldn’t have been feasible without the help of the many people who built custom drivers and documented the steps they took online. This post is my form of repayment; hopefully it will be useful for someone in the future.

Read more...PlaidCTF 2017: Multicast (175 pts)

Apr 23, 2017

PlaidCTF, PPP’s annual capture the flag, was held this past weekend. Because of Google Games and other work, I didn’t spend a large amount of time on it, but I and others on TechSec did manage to solve a few of the challenges.

Multicast was one of the earliest challenges released. We were given two files: a sage program called generate.sage and a file with 20 large integers called data.txt. You can find both of these files and my exploit here.

I listen to more podcasts than you

Apr 04, 2017

You know those people in life who you’re sort of friends with but only talk to when you pass each other in the hallway? You make small talk about what you’ve been up to or some shared interest you have, and then you say “I gotta go to this thing, but it was great seeing to you. Later!” and then never speak to them again until the next hallway-happenstance.

I generally hate these interactions (and I confess that I’ll sometimes take a longer route to avoid them), but I’ve found lately that with with a certain set of people these meetings are bearable because we talk about one specific shared interest: podcasts.

Podcasts have been around forever, but they’ve only taken off relatively recently (mostly due to Serial). Despite their growing popularity, its still a relatively niche form of media: something like 45% of Americans haven’t even heard of the term “podcasting”.

I know this fact because last March was #trypod, a month-long campaign to get more Americans interested in podcasting. Several of the podcasts I subscribe to urged their listeners to recommend a podcast to a friend or post a recommendation to social media with the hashtag #trypod.

Well, March is now over and I never recommended a podcast to anyone, so this post is my form of atonement. I’m currently subscribed to 18 podcasts (and I listen to basically every episode of each one); below I’ve listed each of them along with a brief description of what it’s about and why I enjoy it.

(Don’t know how to get started listening to podcasts? Have Ira Glass teach you by watching this great video.)

Read more...AlexCTF 2017: Catalyst System (150 pts)

Feb 06, 2017

AlexCTF just finished this weekend and our team did pretty well, solving all but two of the challenges. In this post I’ll talk about my solution to one of the reverse engineering challenges, called “Catalyst system.” You can check out the raw binary here.

Read more...MIT Mystery Hunt 2017 [Part 3/3]

Jan 23, 2017

This is part 3 of a series of posts about the MIT Mystery Hunt. You can find part 1 and part 2 here.

I’ll use this last post to talk about the events and the final runaround.

First, the events. There were four of them based on Charisma, Constitution, Strength + Dexterity, and Wisdom + Intelligence. The Charisma event was some sort of speed-dating activity, the Constitution event involved massive bobble-heads that were reused from the Crossing the Charles procession, the Strength + Dexterity event was a human-sized crossover between Hungry Hungry Hippos and Bananagrams, and the Wisdom + Intelligence event was a pub quiz with a twist.

Read more...MIT Mystery Hunt 2017 [Part 2/3]

Jan 21, 2017

This is part 2 of a series of posts about the MIT Mystery Hunt. You can find part 1 here.

This post will attempt to address the two questions on everyone’s minds right now: why was hunt so short, and is this a problem? First, the why.

Why was hunt so short? Well, it wasn’t because there were too few puzzles or metas:

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017

----------------+-----------+---------+----------------

"easy" puzzles | 57 (fish) | 0 | 67 (character)

total puzzles | ~160 | ~160 | ~160

metas | 12 - 15 | 12 - 21 | 15

This year’s hunt had close to 160 total puzzles and 15 metas, about the same as the numbers for prior years. It’s not clear what exactly counts as a meta because of subtleties such as meta-metas, puzzles that reference other puzzles, and puzzlehunts within puzzlehunts, but it’s safe to say that the hunt wouldn’t have been significantly longer had Setec simply included a couple additional character metas.

If it wasn’t the number of puzzles, it must be their difficulty, right? Puzzles that appeared in the character metas were meant to be easier than average, an intentional throwback to the 2015 hunt which included “fish” puzzles designed to be about 1/3 the difficulty of a normal Mystery Hunt puzzle. However, the number of fish puzzles and character puzzles was roughly the same, and the hunt had plenty of difficult puzzles.

Read more...MIT Mystery Hunt 2017 [Part 1/3]

Jan 20, 2017

The 2017 MIT Mystery Hunt ended last Sunday. When I describe the hunt to other people, I often tell them that it’s my favorite weekend of the year, and it is. I get to reunite with old friends, meet new people, and spend 3 straight days solving puzzles. Well, sometimes not quite 3 days, but more on that later.

This was my 6th Mystery Hunt, and the 3rd time I hunted on-site with ✈✈✈ Galactic Trendsetters ✈✈✈. This year we came in 4th, our best performance yet.

The hunt, run by Setec Astronomy and called “Monsters et Manus,” was themed around Dungeons and Dragons. The opening skit involved some D&D players getting sucked into their own game. To get out, they needed to defeat the evil sorcerer Mystereo Cantos (anagram of Setec Astronomy / Too Many Secrets) and recover the two-sided die (the coin!). The hunt structure involved two types of metapuzzles: 6 “character metas,” which were always pure metas and based on the D&D players and their roles, and 8 “quest metas,” which were often shell metas and represented various forays into the fantasy world. There were also 4 events scheduled throughout the weekend that were based on the six canonical attributes of D&D (charisma, constitution, wisdom, etc.). Each of the 6 characters had “levels” that represented how experienced he or she was. Levels could be increased through various mechanisms and puzzles were unlocked based on these levels.

Read more...