The Moon Illusion

Apr 03, 2024In celebration of the upcoming eclipse crossing North America on April 8th, I’ll be posting one eclipse-related post per day. You can see the full list of posts here.

When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie, that’s… an optical illusion that scientists don’t fully understand.

Sometimes I’m driving back home from work and I spot the moon hanging low and yellow over the horizon, and I’ll think to myself “wow, the moon is so big right now.” Other times though, the moon looks smaller, and if I take out my phone and snap a picture of it, it looks tiny.

So, what’s going on? First let’s start with some wrong answers. It’s not because of a supermoon. A supermoon refers to a full moon that coincides with the closest approach of the moon to the earth (its perigee). The moon’s elliptical orbit is very nearly circular, with an eccentricity of only 0.0549, so the size difference is tiny—the apparent diameter of the moon during a perigee is only 14% more than at apogee:

It’s also not because of any purely optical effect like atmospheric refraction. Because the air nearer to the Earth’s surface is denser, the moon (and sun)’s shape can get distorted when they are near the horizon, appearing squashed or stretched.

While this effect does change the shape of the moon, it shouldn’t affect its perceived size. However, it is true that the apparent size of the moon seems largest when the moon is low on the horizon. As it turns out though, this is an entirely neurological effect known as the moon illusion.

The actual angular size of the moon does not change when it is closer to the horizon, but its perceived size does change—it looks much bigger to most humans; in some experiments the perceived size is almost double!

Explanations

If you hold an orange out in front of your face one foot away from your eyes and then extend your arm such that the orange is 2 feet away, it doesn’t suddenly look like the orange has turned into a clementine—our brain automatically adjusts its perception of the size of objects according to how far away they are from us. This effect is known as Emmert’s Law. How do we know how far away objects are? party the answer is depth perception, but there are also a number of monocular clues including motion parallax and accommodation (the ciliary muscles that automatically squish your eyes’ lenses to focus on a farther object send signals to your brain which it can interpret as a depth change).

So, a natural question is: does the moon appear larger on the horizon because our brain thinks its physical size is larger or because our brain thinks its physical distance from Earth is larger (and hence our brain makes the moon seem larger because of Emmert’s Law)? This is where the scientific controversy begins; every so often some neuroscientists will do a study where they try to tease out the difference, but there’s no firm scientific consensus on this issue.

The most popular explanation—and the one that makes the most sense to me—is the apparent distance effect: when the moon is on the horizon we often perceive it next to objects we know are far away, like mountains or skyscrapers. Our brain groups these objects together and comes to the conclusion that the moon is at approximately the same distance away, a distance which our brain thinks is larger than the moon’s distance when it’s above us in the sky.

Why is the perceived distance of a moon in the sky so small? Possibly it’s because our eye lacks any useful cues as to its distance beyond ocular convergence: “it’s far enough away that I don’t need to adjust both eyes inwards at all to maintain single binocular vision, I don’t have any other cues beyond that, so let’s just pick some reasonable default distance for far away objects and use it…” and it just so happens that this default is smaller than the perceived distance of skyscrapers and mountains.

Moon Photography

This still doesn’t explain why when I take a photo of the moon with a phone camera it looks even smaller than it does visually (regardless of where it appears in the sky). This is due to yet another effect: the focal length of the camera lens.

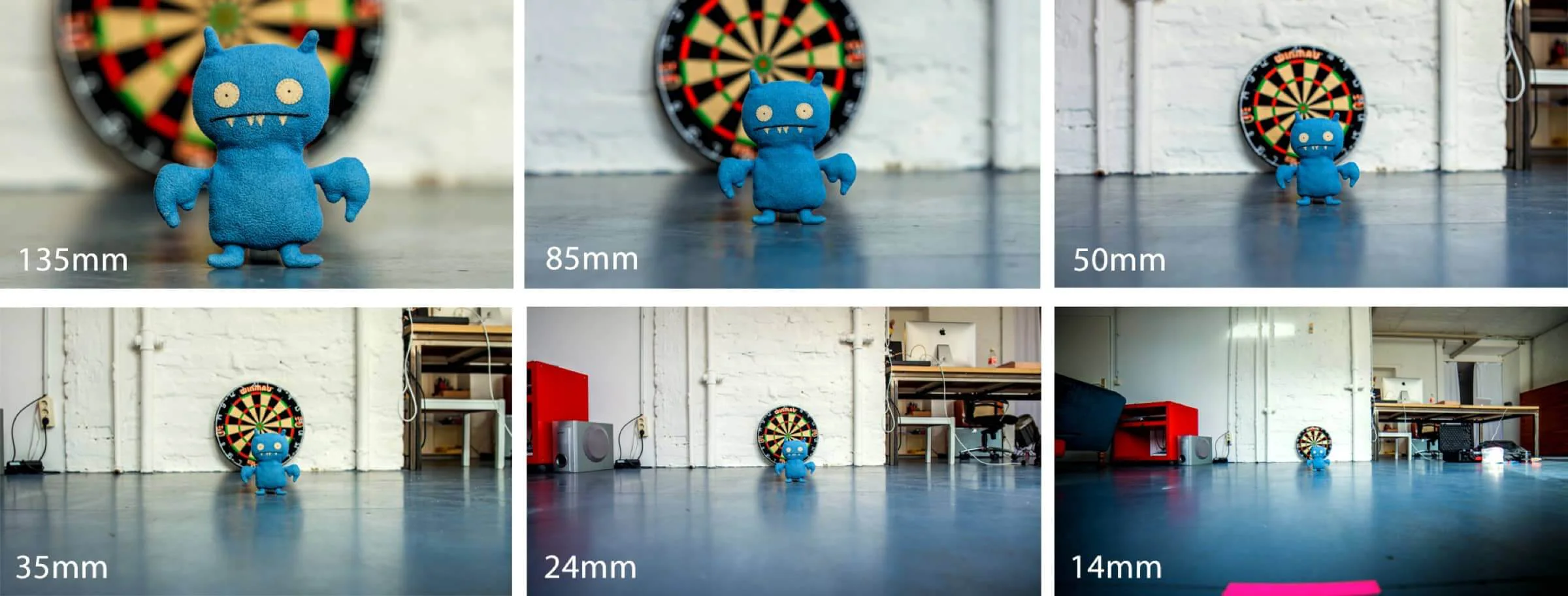

It’s a common misconception that longer focal lengths make objects in the distance appear closer. This is not quite true. Consider the following images, all taken at the same camera position relative to the scene:

Note that the effect is purely magnification—the apparent distance between the blue monster and the dartboard doesn’t seem to change. Now consider the following images, all taken by physically moving the camera such that the blue monster occupies the same percent of the frame in each image to account for the different focal lengths:

Now you can clearly see the distant-object effect: the dartboard appears much further away for shorter focal lengths—but this isn’t directly because of the focal length! It’s because the shorter focal length forces the camera to be positioned much closer to the monster, which then causes the relative distance of the dartboard to be much greater.

In other words, it’s the positioning of the camera that matters—a long focal length just allows you to place your camera far away and zoom in to capture the scene you’re interested in.

What does this mean for capturing great photographs of the moon? Well if you just want a great, high resolution photo of the moon by itself, all that matters is your zoom level / focal length. But if you want a photo of the moon that includes the surrounding landscape, you’ll need to both use a lens with a very long focal length AND position yourself far enough away from the landscape to include it in the frame.

All phone cameras have focal lengths that top out at 77mm at the most, so in practice you’re just not going to be able to capture a photograph like this with your iPhone:

Eclipse Photography

What does any of this have to do with eclipses? Well a solar eclipse is just the moon and sun occupying the same place in the sky, so all the lessons from above apply: because of the moon illusion, the eclipse will appear largest when it’s near the horizon; since the sun is in the same position at the moon, this has to occur nearer to sunset or sunrise. Thus, you’ll have the best experience near the start or end of the path of totality. (This will also result in much less neck strain).

If you want to take a nice photograph of the eclipse, you’ll need a telephoto lens; if you just take out your phone and snap a pic, you’ll get something like this:

which just doesn’t do the experience justice. If this is your first total solar eclipse, my recommendation is to leave the photography to others and just look at the moon and sun for yourself—you’ll only get around 4 minutes of totality and you don’t want to waste time fiddling with your camera.